Heat Networks: from single developments to ambitious area-wide projects, good design and expertise are crucial

Heat networks are gaining momentum, promising cheaper and cleaner energy, but a joined up approach to design and operation are required, says Richard Wilkes, Building Services Associate Director at Meinhardt UK.

It is one of New York’s lesser known landmarks but 601 Lexington Avenue in midtown Manhattan is sure to catch the eye of any skyward-gazing visitor. Its 45-degree sloping roof was designed to contain solar panels, but turned out not to face the sun. Guides on Circle Line boat cruises like to tell tourists the architect was from Boston.

In 19th century London, David Boswell Reid designed what is thought to be the world’s first ventilated heating system for the Palace of Westminster. Although it appeared to work perfectly well, architect Charles Barry did not take kindly to being told how high or wide his towers should be by an engineer ten years his junior. The Lords became sceptical and insisted their House should have a separate system. The building was split below the Central Hall, and the result was that neither system worked properly.

Nearly half the energy used in the UK is for heating, with the vast majority produced by burning fossil fuels (primary natural gas). Heat networks have the potential to contribute to the reduction in the UK’s carbon dioxide emissions as part of a decentralised energy system.

Large scale heat and power projects have continued to have their ups and downs. The obstacles today continue to be less about the technology and more to do with planning, design, operation and cooperation.

In recent history, there have been enough examples of people with limited experience of designing heat networks or understanding of how they operate getting involved. Poor design, inefficient systems and poor maintenance have given the technology a bad press in the UK. Market penetration is tiny here compared with Denmark where as far back as 2000, almost two thirds of heat and power was delivered via heat networks. There, demand was driven by the cost of oil while the UK had plentiful supplies of cheap North Sea gas. The need for lower carbon solutions means the UK is now playing catch up.

Now there is new, policy-driven momentum behind heat networks – and potentially on a bigger scale – in the form of neighbourhood-wide district heating.

Local area/local authority

The main driver for this in the capital has been the London Plan. Heat networks were a key provision incorporated into the London Plan by the GLA, in order to allow decentralised energy solutions to be developed developed for whole districts, to connect up sites as well as one or a number of buildings on a single site.

Studies have been done over the past decade to create heat maps to identify the location of heat loads – demand hotspots – across London. That is because heat networks are more feasible where there is high demand in close proximity so it makes sense to start there. The most promising locations have been identified as opportunity areas and these are the prime focus for local authorities in developing district heat networks. Nonetheless, each new development will be future proofed to allow connection should a heat network be developed in its locality.

Because heat networks are efficient and locally controlled, they can also offer a lower energy price for users. That is attractive to housing associations and some councils. The London Borough of Islington, for example, own and operate Bunhill heat network, and have embraced the technology to reduce fuel poverty for their residents as well as reducing carbon emissions.

Local authorities, working with the GLA, will control the development of area-wide networks. The programme is being developed with large schemes having their own centres but connected to a ring network. That would give back up if one generation centre on the network were to go down, and by connecting different types of building together, the peak loads are evened out, which makes the system even more efficient.

Getting an area-wide scheme started remains a huge challenge. Because local authorities are short of money, they need to find an anchor load to provide a base level of income to start with. A large institutional user or very big residential development is a good start. As an example, one borough is considering relocating a town hall with a CHP plant providing heat to the town hall and surrounding homes, then selling the excess power to the neighbouring hospital.

For local authorities in London, it looks like one barrier to that neat idea is being removed. If you are a heat network operator (private or public sector), the regulations prohibit you from selling electricity, a privilege which is the preserve of energy supply companies. To provide an alternative option, the GLA has made an application to become a junior electricity supplier, which will allow the boroughs to sell electricity to organisations via the GLA. The alternative is to allow an energy supply company to operate the heat network and sell surplus energy for you in return for a commission, although you then have less control over the price that energy is sold at. Not being a profit-driven operation, the GLA is likely to provide that brokerage service for a smaller cut, which will allow local authorities to sell the heat more cheaply to their residents.

Individual developments

New developments are required by planning regulations to have heat networks, and as more and more residential scrapers reach skywards across the capital, most of London’s new housing schemes, as well as its non-residential developments, are well suited to the concept. However, it is harder to implement for traditional rows of houses.

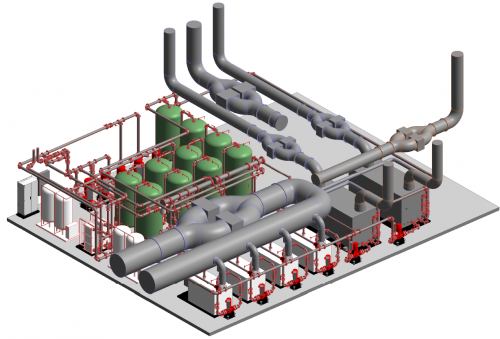

At the project scale, heat networks are designed to serve multiple buildings – or multiple units within a building – from a central location. So rather than each apartment in a block of flats having its own boiler, one energy centre serves the entire block. It is more efficient, and easier to incorporate low and zero carbon technologies, although there are some distribution losses.

As more efficient and lower carbon ways of generating heat and power develop in future, systems can be more easily upgraded by replacing the generator in one central location rather than, for example, replacing 400 boilers in 400 flats. There are also benefits in security of energy supply as standby plant can be incorporated into the design of the energy centre.

Combined heat and power networks provide electricity as well as heat, and because electricity is generated locally, there are not the massive losses from the long distance grid network.

There are advantages for build-to-rent operators because there is only one central location to monitor rather than having to make hundreds of apartment visits to inspect individual boilers. Larger build-to-rent operators can operate energy centres themselves but will have to outsource to an energy supply company if they want to sell electricity beyond their development.

With the drive towards carbon reduction, bio fuel CHP units are available, but these are generally more suited to locations closer to the fuel source.

Clearly, if the UK is to adopt heat networks on the scale of Denmark, there are obstacles to overcome. We believe it will not be easy but that it is possible.

At Meinhardt, we have experience of acting as consultants on prospective area-wide schemes in London as well as on big development projects incorporating heat networks.

To tackle the image problem of heat networks, we welcome recent initiatives by the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE). In response to the problem of poor design and installation of heat networks, CIBSE has developed a code of practice. A training and approvals scheme allows successful candidates to become registered heat network designers.

One reason systems can fail is that designers are not always in contact with the people who are running systems after completion. It is difficult to design without knowing how a system operates in practice. We worked alongside energy consultants and the technical team from London Borough of Islington to produce an energy and services masterplan feasibilitystudy for the Whitechapel regeneration masterplan on behalf of London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

The resulting report was really well rounded because of the practical experience of the team.

Meinhardt already has substantial experience of implementing networks for large scale developments. We are currently working on a 2,000-home build-to-rent development at Greenford Green, and have designed the network and energy centre as well as beginning negotiations with potential energy supply companies who may operate the system and sell surplus energy on our clients’ behalf. That project is an example of an anchor load that could kick start an energy network for that area.

Conclusion

London Mayor Sadiq Khan shows every sign of carrying on his predecessors’ energy policy, and although there are challenges, the direction of travel towards decentralised energy distributed via heat networks isn’t likely to change.

Private and public sector operators of heat networks need large scale demand to get the economies that make their installations viable. That means supplying heat and power at a competitive rate and gaining the confidence of customers. Doubts about continuity of supply, if it is threatened by technical issues or perhaps even security concerns, will soon have commercial customers looking for alternatives.

The London Plan is driving the concept forward but networks have to be realisable and affordable. For developers, local authorities, customers and London as a whole to benefit, good design and a joined up approach to planning and operation will be crucial.